What does it mean to understand financial accounting? Many surprisingly learned people spend the better part of a lifetime developing an understanding of accounting but, in fact, perhaps 80% of such accounting knowledge--the knowledge used by practicing accountants routinely, everyday--can be summarized as follows ...

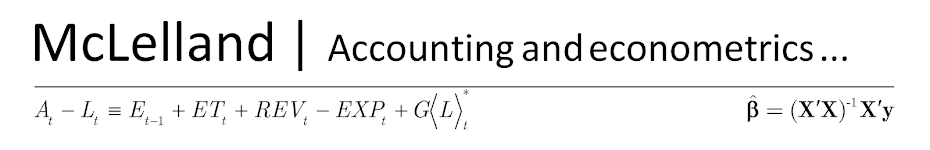

(1) The fundamental structure of financial accounting:

... where ASSETS represents the accounting value (see (2), (3), and (4) below) of economic resources controlled by the firm; LIABILITIES represent actual and estimated non-ownership claims against the firm's assets; EQUITY represents owners' residual claims to (net) assets; EQUITY TRANSACTIONS basically represent payments to and from owners in exchange for changes in owners' equity claims; REV represents the accounting value of products and services sold to customers in ordinary operating activities; EXP represents the accounting value consumed in ordinary operating activities; and G<L> represents non-operating gains (lossses) resulting from any change in net assets (A(t) - L(t)) not associated with ET, REV, or EXP.

(2) The historical exchange price principle:

Economic exchanges--between unrelated parties who are not compelled to enter the exchange--are measured at the clearer (i.e., more accurate and precise) of the estimated fair market value of consideration (i.e., something of value) given or of consideration received; and such values are assumed to be equal:

The value is formally called the historical exchange price (HEP).

The value is formally called the historical exchange price (HEP).

(3) The revenue recognition principle:

Setting aside accounting period technicalities, revenue recognized in the financial statements for a product or sales contract through time t is determined by the following revenue recognition function:

... where it is important to recognize that each of the three factors on the right-hand side of the expression are almost always either estimates (preferably) or assumptions (less preferably).

(4) The expense recognition principle:

Again setting aside accounting period technicalities, expense recognized in the financial statements for a particular resource or set of resources through time t is determined by the following expense recognition function:

... where it is important to recognize that each of the two factors on the right-hand side of the expression are almost always either estimates (preferably) or assumptions (less preferably).

(5) The disclosure principle:

Accounting principles and methods used by the firm—as well as descriptions and details of financial statement components, and other financial matters relevant to users—are fully disclosed in the financial statements.

So, understanding basically comes down to understanding the fundamental concepts and structure of financial accounting, and four fundamental principles. There are, of course, other "principles" such as the "conservatism principle", but these have been omitted because they are not universally applicable in all countries and are not even consistently applied across accounting standards within individual countries.

_________________

No doubt the reader finds the above outline quite kōan-like. This is intentional: It really is as simple as outlined above, but it does require thought to understand accounting this way; examples are good but words seem to just get in the way. Here's an accounting koan of sorts, mentioned in a previous posting, and a semi-cryptic discussion of it:

If my company pays $100 cash for an ordinary pen that can easily be purchased for $1 at any office supply shop in the area, how should my company record the exchange?

Most accountants will simply answer the question by saying the acquired pen should be recorded at the amount paid for it. When asked why the exchange should be recorded in this way, most accountants answer that it is a simple application of the "historical cost principle". It turns out that neither answer is correct: The proper accounting measurement of the pen depends on certain economic characteristics of the exchange and of the buyer and seller, and the “historical cost principle” actually does not suggest the pen be measured at $100 for accounting purposes. So, the accountant (or manager) knows how to record the exchange given that the measurement is correct, but actually does not know how to determine the proper measurement.

This is but one simple example of how understanding accounting mechanics—so-called, “debits and credits”—does not provide accountants or managers with an adequate understanding of accounting concepts and principles, which is in fact a necessary prerequisite for understanding accounting methods in general.

I'll give examples applying each of the principles--examples of accounting methods and mechanics--in future postings ...

MMc

São Paulo

Malcolm,

ReplyDeleteTo help me better understand your example regarding the pen transaction, can you provide an example of a certain economic characteristic of the exchange and the proper accounting treatment from it?

Well, I actually need to write another post (and I will) titled "The historical exchange price principle" which will explain what conditions of the exchange are important. But most simply put it's this: If the exchange is conducted under conditions that might reasonably be characterized as a "fair market", then (for reasons I'll explain later) it's reasonable to assume the value of what was given is equal to the value of what was received in the exchange.

ReplyDeleteSo in the (very unlikely) event that the example exchange had all the important characteristics of a fair market exchange, then it's reasonable to assume the value of the pen is $100, not $1.

It's actually quite a subtle concept. I've found that although most people (accountants included) think the so-called "historical cost principle" is the easiest principle to grasp, it's actually the most difficult because it requires one to understand what a fair market is.